Video Teaching

Audio Teaching (Downloadable)

Study Notes and Slides

Tefillah Part 4 - Fixed Prayer The Amidah Shemoneh Esreh

Today, we are going to look at the Amidah prayer. The Amidah means, “The Standing,” denoting the preferable posture one adopts when saying this prayer. It is also known as the Shmoneh Esreh, which means “The Eighteen,” named after the original number of phases in the prayer.

The Origin of the Amidah

But before examining the Amidah, we must first focus on how it came about. Its author is attributed to Ezra the Scribe and what’s known as Anshei Knesset HaGedolah (the Men of the Great Assembly).

Ezra was a Scribe and Kohan. He was a descendant of Seraiah (Ezra 7:1), the last Kohen HaGadol to serve in the first Bait HaMikdash (2 Kings 25:18) and he was a close friend of Yahshua HaKohan, who was the first Kohan HaGadol to serve in the second Bait HaMikdash (1 Chronicles 5:40-41). Ezra was the chief driving force in reintroducing and reinforcing Torah observance in Yerushalayim after returning from the Babylonian exile (Ezra 7-10 & Nehemiah 8). Some manuscripts say he was a Kohan HaGadol, others say that he was just a regular Kohan.

His name is an abbreviation of עזריהו Azaryahu, “Elohim-helps.”

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah are interlinked. Originally, they were one scroll, but later split into two, one being called Ezra and the other Nehemiah. Nehemiah worked to rebuild the city of Yerushalayim and Ezra worked to rebuild the people.

No other Jew in history has been as influential in structuring the format of Judaism as Ezra.

Ezra’s assembling of scholars and prophets to form the Great Assembly was the forerunner of the Sanhedrin, which was the authority on matters of religious law, following in the footsteps of the 70 elders ordained by Moshe Rabbeinu. The Men of the Great Assembly were credited with establishing numerous features of contemporary traditional Judaism in something like their present form, including which books would be included as “cannon” within the TaNaK, Torah Readings, the Amidah, the celebration of Purim, synagogal prayers, rituals, Kiddush, Havdalah and various other benedictions. Ezra and this council comprising 120 learned men did more to actually shape the way Torah was observed than even Rebbe Yahshua.

The prophets Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi were on the council and bridge the gap between the era of prophets and the Men of the Great Assembly.

The Talmud (Megillah 17b) teaches that Ezra and the Men of the Great Assembly composed the eighteen blessings of The Amidah in the early years of the Second Temple Era. So, the Amidah is a prescribed prayer that is over 2000 years old.

Its conception is linked to a key event in the history of Yisrael. The core of the Amidah is its strong references to redemption and the engine of redemption fully ignited only after the nation begun to audibly groan. After Moshe killed an Egyptian and the current Pharaoh died, giving rise to an even crueler one, we read,

“And it happened that during those many days that the King of Egypt died, the Children of Yisrael groaned because of the work, and they cried out. (Exodus 2:23)” Even though Yisrael had been slaves and endured many hardships long before this point, they suffered in silence and did not pray, as words only follow understanding (binah). Yisrael had been born into slavery and up until this point, the nation had no knowledge of any other way of life. Not only were their bodies enslaved, but their power of expression was also very much enslaved.

Moshe demonstrated that a superior lifestyle existed and the people came to recognise their pain and called out to Elohim for redemption. The redemptive process begun to take full flight only after the nation collectively recognised that there was a need. They emerged from being enslaved and silent to being a vocal people. But they were unable to clearly articulate their needs. That’s why the verse says “groan” and “cry.” But this is all Yah requires. As Rav Sha’ul (A.K.A. Apostle Paul) puts it,

“…the Spirit helps us in our weakness. We do not know what we ought to pray for, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us through wordless groans. And he who searches our hearts knows the mind of the Spirit, because the Spirit intercedes for Elohim’s people in accordance with the will of Elohim. (Romans 8:26-27)” But, and this is a big, but, as we grew, not only as individual people in our own lives, but as a body of people that grow from generation to generation, we most move from a groan to words and from words to more meaningful words.

Man’s challenge, therefore, is to fashion his personality, to arrange his hierarchy of values so that he can discover and identify his needs and cry out for them. The silence moves from a groan to articulate speech.

Problem is not every believer lives on this earth in an equal set of circumstances and not everybody has the knowledge and understanding to recognise all his potential needs and articulate them clearly.

The Men of the Great Assembly faced the very real threat of losing valuable knowledge of how to observe the Torah, with the loss of so many great men and women. Added to this the absence of the Temple service meant that something had to be done to echo its function in the daily lives of individuals.

While the Shema is the jewel in the crown of fixed prayer, the Amidah is the crown.

The Amidah is the most important prayer ever written. It’s no coincidence that the famous Lord’s Prayer as handed down by King Messiah Yahshua is based on the same pattern as the Amidah. So why is it deemed the most important prayer ever written?

Imagine that one hundred and twenty of the greatest computer scientists in the world are brought together and given unlimited access to the most advanced technology available to write a program for a supercomputer designed to remain state-of-the-art for all time. They are joined by visionaries able to discern every possible requirement of the future generations of computer users. This portrayal, if it where it ever possible, is but a glimpse of the extraordinary process which culminated in the sacred and ever-powerful words of the Amidah.

In the 5th century B.C.E., the 120 men of the Great Assembly composed the basic text of the Amidah. The exact form and order of the blessings were codified after the destruction of the Second Temple in the first century C.E. The Amidah was expanded from eighteen to nineteen blessings in the 2nd century C.E., under the leadership of Rabbi Gamliel the Elder in Yavneh. The additional blessing (against heretics) was initially meant to combat the threats posed by the Samaritan, Sadducee, and Nazarene sects of Judaism. But more on that later.

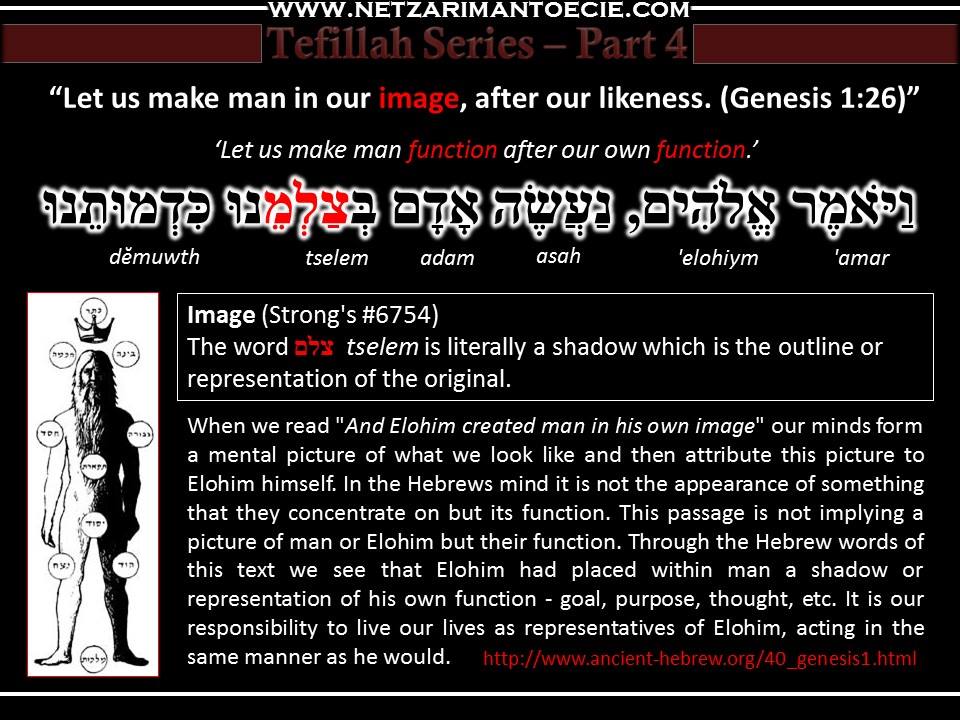

The Torah tells us that Yahweh declared, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. (Genesis 1:26)” Most Western minded people immediately think of a physical image, but the verse refers to function alone. So it is better translated as, ‘Let us make man function after our own function.’ Yahweh wants man to join him in the process of creation and development. The physical act of circumcision symbolises this unique and privileged role.

The primary purpose of prayer is not to change Elohim, but to change us. Man cannot solve his problems or satisfy his needs alone, nor can he ignore them. Torah rejects the notion that we should suffer in silence, rather the Torah wants man to cry out to Elohim to rescue him from affliction.

“Whoever calls in the name of Yahweh shall be saved (Acts 2:21; Romans 10:13; cf. Joel 2:32[3:5])” These verses are connected to the Torah, were it says, “Then all the peoples on earth will see that name of Yahweh is proclaimed over you, and they will fear you. (Deuteronomy 28:10)” (Click) So this means, those who have Yahweh’s name on them, evident in their collective uniform conduct. There is no such thing as disorganised religion. Where there is no order, there is anarchy. In every vocation, there needs to be leadership and structure. There needs to be a group of people that identifies clarifies and prioritises the needs of the masses. Enter the Shmoneh Esreh, introduced to us by the Men of the Great Assembly as a litany of specific requests, designed to classify every need.

The development of a fixed prayer, moreover, allows the worshipper not only to be aware of his sundry needs – spiritual dietary, financial, emotional, and so on – but to understand how to respond to them. They must be channelled properly, toward the service of Elohim, as expressed by King Solomon, “In all your activities, know him. (Proverbs)”

The Avinu in Brief

As Nazarenes, we have a special connection to the Avinu tefillah otherwise known as The Lord’s Prayer, but we cannot hope to appreciate this short and seemingly simplistic prayer until we delve into and understand the structure of its precursor, the Shmoneh Esreh.

The most fascinating thing about the Lord’s Prayer, the prayer the Messiah told us to pray, is that it’s actually pretty ordinary. It carries nothing out of the ordinary than any other Jewish prayer that has ever been formulated. In fact, every aspect of it is woven from the same raw material as every other Jewish prayer that’s ever existed. Note how it comes about in chapter 11 of Luke.

“One day Yahshua was praying in a certain place. When he finished, one of his talmidim said to him, “Adonai, teach us to pray, just as John taught his talmidim. (Luke 11:1)” Did you notice what was said? “…just as John taught his talmidim.” This is amazing, because it shows us a tradition of a signature prayer that was taught by rabbis to their students. What was John the Immerser’s prayer like? We have no Scripture on John’s prayer, but we have some further interesting information that confirms a tradition of prayer that was observed across sects of Judaism. (Click) “They said to him, ‘John’s talmidim often fast and pray, and so do the talmidim of the Pharisees, but yours go on eating and drinking. (Luke 5:33)’” Author and Messianic teacher Aaron Eby says that there is nothing in the Avinu that would make it uncomfortable for a Jew to pray outside the fact that it’s so centre within Christianity. All its components are derived and patterned after Jewish prayer and it has nothing in it that makes it particularly distinctive in any way.

For those of you curious about the prayer that John may have taught. This is what I managed to find. This is from an old Syriac manuscripts contains a possible rendering of John’s prayer. It reads: “Holy Father, consecrate me through your strength and make known the glory of your excellence and show me your son and fill me with your spirit which has received light through your knowledge."

Now, the big question is this. Did Yahshua teach the Avinu as a substitute for the Amidah. The answer is no. Why? Because many great rabbis throughout history have taught original prayers to their disciples as prayers that uniquely connect them to their rabbi and at no time were any of these prayers introduced to cancel out any fixed prayer handed down from the days of Ezra.

How to Recite the Amidah

Before we look at the Amidah itself, we must first discuss how the prayer is articulated. We recite the Amidah in an undertone. Not a whisper, but a faint voice. This is to contrast the Prophets of Ba’al who called out loudly to their Elohim, but were ignored. Now this might sound like a bit of a contradiction as indeed we are commanded to “call in the Name,” but this is not speaking about volume so much as it is about the act of calling. It was the mother of the Prophet Samuel, Channah, who first displayed the most intensity in praying in 1 Samuel 1:12-16. Channah prayed without being heard, because she was so immersed inner concentration. She even fooled a Tzaddik, who was not familiar with such a style of prayer until he saw her. “As she kept on praying to Adonai, Eli observed her mouth. Hannah was praying in her heart, and her lips were moving but her voice was not heard. Eli thought she was drunk and said to her, “How long are you going to stay drunk? Put away your wine.” “Not so, my Adon,” Hannah replied, “I am a woman who is deeply troubled. I have not been drinking wine or beer; I was pouring out my soul to Yahweh. Do not take your servant for a wicked woman; I have been praying here out of my great anguish and grief.”

How to Stand During the Amidah

Next is posture. We are to stand if we are able throughout its entire recitation facing East. The whole Amidah can take as little as 7 minutes if read quickly and up to 30 minutes if read with slow concentration. While reciting this lofty prayer, we stand with our feet together as explained in the Talmud (in Tractate Berachos 10b). This suggests that we are like angels, whose feet are always together. (Yerushalmi Berachos 1:1) There is no more room for movement, as we are within the innermost chamber before Elohim. We have arrived. Our feet are as if together, also signifying that we have completely surrendered our sense of separate self, and we are bonded with the Eternal. (Rashba ibid.) This transformation encompasses our entire being, and a total metamorphosis takes place, of our orientation to the right (to Elohim) as well as of our orientation to the left (to the ego), both of which are now joined together, connecting with Elohim in unison. (Mabit)

Approaching the Amidah

Before we pray the the Amidah, we take three steps backward, and then three steps forward.

This is done to enhance our concentration and stimulate greater focus. The movement forward indicates and symbolises our entry into the Creator’s innermost chamber. Thus we symbolically enter a sacred space in which we can, if we truly desire, encounter Elohim’s presence.

The number of steps is highly significant, as the three steps mimic the three steps Moshe took when he entered prayer, as he travelled past the three partitions—the darkness (choshech), the first cloud (anan) loud and the second cloud (arafel)—before he encountered the Divine.

Mentally, we should visualize ourselves moving into the Holy Land, with the first step, then into Yerushalayim/Jerusalem with the second step, and into the Temple with the third step, thus standing on the threshold of the Holy of Holies.

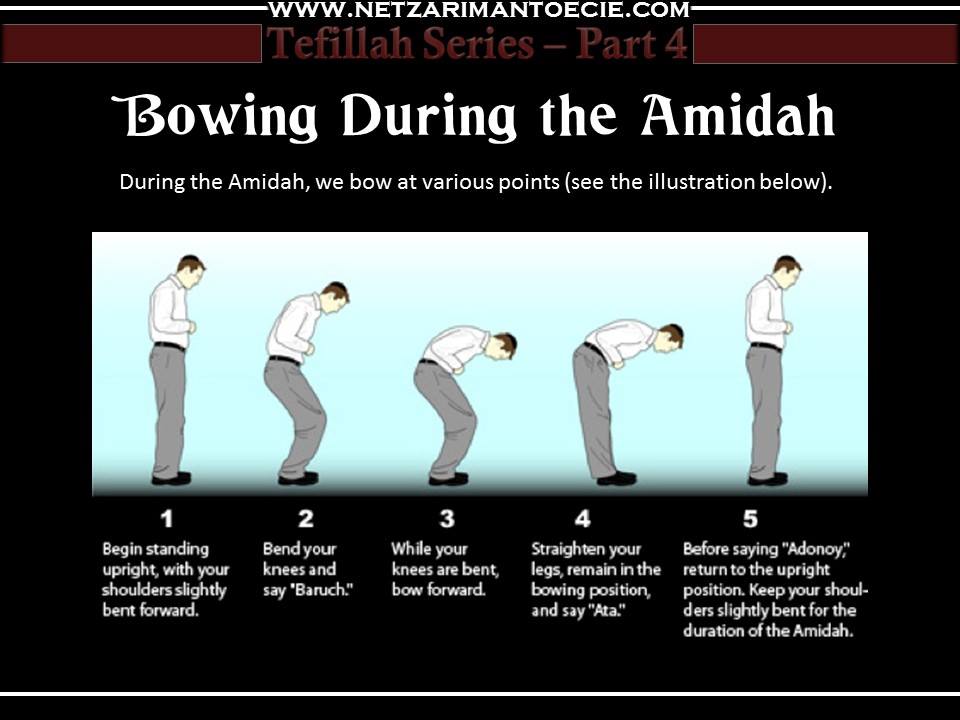

Bowing During the Amidah

During the Amidah, we bow at various points (see the illustration above).

1. At the opening of the Avot blessing, at Baruch, bend the knees.

At the second word (Ata), bow from the waist.

At Hashem’s Name, stand erect.

2. At the end of Avot (Magen Avraham), we repeat the procedure:

At the opening Baruch, bend the knees.

At the second word (Ata), bow from the waist.

At Hashem’s Name, stand erect.

The Content of the Amidah

The Amidah is made up of various blessings. The first three blessings are praises, the middle portion are requests, and the final three blessings are thanksgiving in nature. The Talmud (Berachos 28b) teaches that this recital of eighteen blessings corresponds to the eighteen times Yahweh’s name is mentioned by King David in Psalm 29. The eighteen also draws a parallel to the eighteen times our forefathers are mentioned together in the Torah.

1st Blessing - The three patriarchs, Avraham, Yitzchak and Ya’akov are mentioned in the first blessing to denote a unique personal discovery of Yahweh’s relationship with man. Each one laboured in his own way to find the most effective way to serve Elohim. Avraham represents kindness, Yitzhak, introspection and Ya’akov, the pursuit of truth.

2nd Blessing – Elohim’s Might – This blessing expresses Yahweh’s unique might by describing miracles that can only be attributed to Him alone, such as His ability to resurrect, destroy life and Create life.

3rd Blessing – Elohim’s Holiness - In the Kuzari, a classic medieval work by Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi, he classifies creation into five groups: inanimate objects, vegetation, animals, man, and the Nation of Yisrael. Yisrael reside at the top of the chain, because at Mount Sinai, Elohim designated us “a kingdom of Kohanim and a Kadosh nation. (Exodus 19:6)” The nation od Yisrael was chosen to lead the world to understand and comprehend Yahweh’s mission. We do this being imparting sanctity in all we do. The declaration that “You are holy” communicates our readiness to sacrifice all, even our lives if need be, to sanctify Elohim’s Name.

4th Blessing – Sekel, intelligence is the essence of what makes us human and we must recognise that our intelligence comes from Yahweh. For one to accept a gift and misuse it is the ultimate ingratitude; therefore, we must not channel our intelligence toward areas of study and endeavours that are devoid of holiness or immoral or unethical.

We are essentially praying that we correctly understand situations and information. The Torah is expansive and intricate and often difficult to penetrate and to retain. We mention the concept of da’at (knowledge) during Havdalah, because without it, we could not discern between Shabbat and weekdays.

5th Blessing – T’shuvah. Once we understand correctly, we then are moved to acknowledge our own inadequacies.

6th Blessing – Forgiveness (Strike the left side of the chest with the right fist while reciting) Forgive us, our Father, for we have erred; pardon us, our King, for we have willingly sinned; for You pardon and forgive. Blessed are You, Yahweh, the gracious One Who pardons abundantly.

7th Blessing – Redemption – Often the various difficulties we experience in this world emanate from our inappropriate actions and sins. After doing t’shuva and asking for forgiveness, we now ask for the difficult situations in our lives to be reversed.

Behold our affliction and take up our grievance, and redeem us speedily for Your Name sake, for you are a powerful Redeemer. Blessed are you, Yahweh, redeemer of Yisrael.

8th Blessing – Health & Healing – Often people only pay attention to their health when specific ailments appear and only then do they realise how fortunate they had been to be blessed with good health, enabling them to function.

A doctor may treat two patients for the same ailment using the same medication, yet one will be cured and the other will succumb to the disease. In the former case, Yahweh decreed that he be cured and the latter, not. The blessing of healing comes at the eighth stanza, because the mitzvah for circumcision occurs on the eighth day. Seven corresponds to the natural world, but the number eight, the eighth day corresponds to circumstances that are beyond the realm of the norm. So we request that Yahweh go beyond normal physical limitations to heal.

9th Blessing - Prosperity